|

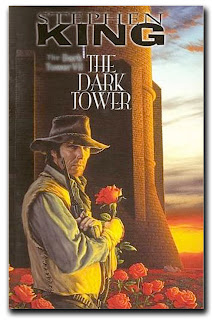

| Roland, the last gunslinger, as painted by Phil Hale in The Drawing of the Three |

Following the earlier entries on different volumes, the below attempts to sum up some impressions and thoughts about Stephen King's The Dark Tower novels.

Needless to say, there are spoilers aplenty. If you haven't read the books and want to learn what happens in them the old-fashioned way, then you should probably stop reading pretty quickly.

-----

-----

By the time he'd finished, he'd become a husband, a father, a successful author, a brand-name franchise writer and even a grandfather. Obviously, over time his perspectives and thoughts changed. King himself observes the length of the journey in an author's note to volume four, Wizard and Glass, when he points out that a very young man, much more like the boy Roland was at the time, wrote the scene just before a door opens at a particular point. A much more mature and presumably wiser one, who is a lot more like Roland's father Stephen, wrote the scene just after the door opens.

At a million-plus words, the Dark Tower saga is justifiably knocked for being something on the puffy side. As early as the second book, though, King said the whole thing was very likely to be six or seven books long.. But I'm going to guess that the six or seven books he projected when writing The Drawing of the Three in the mid-1980s were not exactly the seven that wrapped up with The Dark Tower in 2004. I think at some point in the series, King's vision of what he was trying to do with this long work, inspired by Robert Browning's poem "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came," changed dramatically. At some point in this process, the Dark Tower saga became something entirely different than it was when he started -- and not, to be honest, for the better.

1. The Good

Before we get to that, there are a wealth of fascinating concepts at work in the series. When we first meet Roland, he's pursuing the Man in Black across a vast desert in a world that has, we're told, "moved on." Although it'll be awhile before we get a clearer picture of the causes of this moving on, we see it seems to feature a lot of abandonment, a loss of vibrancy and color and a breakdown of some kind of the natural laws we depend on. I noted that the mall where I originally purchased Drawing has lost its anchor stores and most of its retailers; to walk around in it now, nearly alone, past empty windows and storefronts, it to get a sense of something that has moved on.Abandoned malls and shuttered factories aren't the only things that can project this air of moving on. Even though our culture seems to be speedier, brighter and flashier than ever, we can see a loss of connection among families and in our communities brought about by greater mobility and self-sufficiency. It's a fascinating idea about how a culture or even a world may come to an end -- not by fire or by ice, not from bang or from whimper, but with the simple sign "Closed," or even no sign at all, just an empty window.

The end of Roland's quest, which turns out to be the beginning of yet another cycle of endlessly repeating his search for the Tower, is another intriguing idea. My post on Book 7 compares the idea with C.S. Lewis's vision of hell in The Great Divorce. The damned receive exactly what they've dedicated their lives to winning, only to learn that without the presence of God, everything is damnation. I've read some commentary that suggests the sentence to a potentially endless repetition of the quest is unjust. Yes, Roland sacrificed relationships and even people, sometimes without much compassion or regret, in order to continue his journey to the Tower. But he was trying to reach it to stop the Crimson King from destroying it and plunging the multiverse into chaos, the argument goes, so he had to make some hard choices. Roland and Eddie make this idea more or less explicit to Jake in The Waste Lands when the boy wonders if they can't stay a little at River Crossing and help the old people there before traveling on. If they allow themselves to be distracted by the real needs these people have, they'll wind up distracted by so much they'll never reach the Tower.

Except that when we first meet Roland, he does not yet know about the danger facing all the worlds, including his own. His goal, we learn in The Gunslinger, is to reach the Dark Tower, climb to its top and question "whatever god may dwell there." There's no agenda of saving anything, and it's in service to that quest he sacrifices Susan Delgado in Wizard and Glass and Jake Chambers in Gunslinger. It's while on that quest that he kills Allie, the bartender in Tull with whom he shares a bed -- and in the original version of Gunslinger, he kills her when she's been grabbed as a human shield, not because she's been driven insane by the Man in Black and begs for the mercy of death as happens in the revised edition. Though the ka-tet that surrounds Roland later in the series humanizes him and he learns his quest was not for his own satisfaction, things don't start that way and Roland has earned his journey through the purgatory of repetition.

2. The Bad

So what about the series is bad? The smart-aleck answer is, "About four-fifths of everything that comes after The Drawing of the Three." The Kingophile Tower-head answer is, "It needed to keep going."My own pet peeves about the later volumes of the Tower saga relate to its length, but they have more to do with its bloatedness -- even properly edited, this would still be a long work so the length is less of a problem than the sprawling mess. But that's been covered here before, so not much else needs to be said about it.

For my money, the real fatal flaw of this series comes in Wizard and Glass, which I've already said I see as its lowest point. Brief recap: The ka-tet outsmarts the murderous monorail Blaine but finds themselves in a world without a Beam to follow to the Tower. Now in the Kansas of this world, most probably the world of King's The Stand, they walk towards an odd-looking city of green glass astride Interstate 70. After a loooong flashback describing Roland's first love and first glimpse of the Tower in a magical seeing-stone, the ka-tet faces down the Man in Black in this faux-Emerald City and returns to Roland's world, where they can see the Beam again and renew their journey.

The Emerald City vs. Kansas setup is an obvious nod to the movie The Wizard of Oz. Dorothy Gale's words when she wakes up in Oz -- "I don't think we're in Kansas anymore" -- are a catch-phrase cliché and King seems to mean them to have a large impact on how the latter half of the Tower saga will run. It's in the books following Wizard that he begins to emphasize certain things, like the recurring presence of the number 19. It's also where he starts to make the sources of some of his authorly ideas more explicit, like the Doctor-Doom inspired, light-saber wielding Wolves in Wolves of the Calla or the explosive sneetches that are patterned after the golden snitch of Harry Potter's Quidditch game. Writers draw their inspirations from all kinds of places, and the fun some fans have with their books is trying to figure out what those inspirations were, as well as how their use may convey meanings the author wants to communicate. Pre-Wizard, King talks about those inspirations in interviews about the Dark Tower books. Post-Wizard, King talks about them in the books themselves -- sometimes directly, since he shows up in person in the last two.

It seems to me that the first three books of the Tower saga, as well as the long Meijis flashback in the fourth, are all stories about Roland's quest for and journey towards the Dark Tower. The last three are stories about the story about Roland's quest for and journey towards the Dark Tower. When we enter the faux-Emerald City with Roland and the ka-tet, we're still inside a narrative, in other words. When we leave it, we're now inside a kind of meta-narrative that will have our original story as a feature rather than the centerpiece. I have a friend who's a devoted Kingophile who says that after he read Wizard and Glass, he started thinking that King really had no idea where he was going with the Tower saga. I think that's partly true.

I think that from the beginning, King knew Roland's quest for the Tower began with Roland alone and would end the same way. Others who would join him might die like Eddie and Jake or they might leave like Susannah, but they wouldn't reach the Tower with him, even if King himself didn't know from the start the details of their entries, exits and travels in between. I think that early on in the series, King probably thought that the tale would end with Roland at the Tower door. I don't think he envisioned anything afterwards until maybe the middle books, when the idea of the endless quest took shape.

But at some point between The Waste Lands and Wizard and Glass, King's vision of the Tower saga changed from a narrative vision to this meta-narrative-styled one. And while he sort of knew how the narrative should finish, it took until well after Wizard and Glass before he could figure out how the meta-narrative would carry it there. On the one hand, the idea that Roland returns to an earlier stage in his quest is really the only way for the last gunslinger's story to end. I can't imagine that more than a small slice of the true-blue Tower-head fanbase would have been happy leaving Roland at the door of the Tower and not seeing what was inside it. Witness how many fans of the TV show Lost complained that the show's finale never really said what the island was or why it was important or something similar. I don't think King believed he could get away with that kind of a finish, even though I think it probably would have been a good one. And King has sometimes struggled with ending his stories as well as he's told them. Even if he hadn't, what in the world could have been inside that Tower that would have been a fitting prize for the quest that's preceded it? My imagination's pretty good and I can't even begin to answer what Roland might have found that would live up to what I think should have been there after seven books and more than 30 years worth of work.

On the other hand, Roland's return to an earlier point of his quest is a nice fit with the idea that the Tower saga has become a meta-narrative on how the imaginations of artists or writers relate to the works they create. The story has been told; the work completed, the door into this imaginary world closes. What's next? Well, for artists and writers, the only real "next" possible is another creation, another story, another world to explore via their imaginations and visions. So Roland returns to where we first meet him, setting out across the Mohaine Desert after the Man in Black. Both the story and the process by which it is told begin anew.

The meta-narrative idea shapes other parts of the story as well. Rather than the Man in Black being of a similar villainous type as The Stand's Randall Flagg, the two characters became one. In 1987's The Eyes of the Dragon, King hints that Flagg has lived in more than one world, which may be one of the earliest signs he's started to re-think the Tower saga along meta-narrative lines.

Other characters and ideas from the Tower saga doffed their other-novelish outer clothing and became overt representations of their Tower-world identities. Ralph Roberts and Lois Chasse battle the Crimson King's agents in Insomnia in order to save Patrick Danville, who will help Roland defeat the King in The Dark Tower. Breakers Dinky Earnshaw and Ted Brautigan show up in the "Everything's Eventual" short story and "Low Men in Yellow Coats" novella, respectively. 'Salem's Lot's disgraced priest Don Callahan travels through the worlds of King's multiverse, slaying and fleeing from vampires until those same Low Men chase him into Roland's world at Calla Bryn Sturgis. Stephen King himself becomes a character in Song of Susannah and The Dark Tower as an author whose writing of the Dark Tower saga is vital to the completion of the ka-tet's Dark Tower quest.

These and other connections all serve to make an obvious statement: One guy, Stephen King made these characters up and wrote their stories. Well, duh. That's whose name is on the covers and whose picture is on the dust jackets. That's who talks about them with interviewers and persistent fans. But for some reason, it seems King chose to tell the last half of the Tower saga in a way that, as I said above, makes it a story about the story instead of a story itself. As much as I dislike the Meijis flashback in Wizard, it's just about the last sustained burst of pure narrative in the series. Even the superior Wolves of the Calla starts to show symptoms of meta-narrative-stisizing; It's where where the number 19, which was previously not at all a factor but which started to be important after King was seriously injured in a van-pedestrian accident on June 19, 1999, starts to recur. It's where Callahan shows up, where King's earlier novels appear within his own books both as novels and as descriptions of what the characters see as actual events, where his authorly in-jokes disdain any subtlety and proudly show off their own punchlines, and so on.

When we leave the faux-Emerald City and return to Roland's world, we make dual shifts. By leaving The Stand's Kansas, we leave the scene of one of King's earlier, straight-up, tell-the-story novels for what will become a journey through this meta-narrative stuff that makes the second half of the Tower saga seem like one long Little Jack Horner self-analysis. But at the same time, we also leave behind the flight-of-fancy Emerald City of a conceit that novels are their own stories and their characters command their own destinies through the writer's keyboard, and we enter the Kansas-styled prosaic reality that novelists write novels using their own imaginations, experiences, memories and ideas. The last book has a good example.

Dandelo, the psychic vampire, threatens to kill Roland and Susannah by feeding on their emotions before they're aware of their danger when they stop to stay at his cabin in the land of Empathica. The author Stephen King has the character of the author Stephen King leave Susannah a note warning them about Dandelo so she can kill him. It is, the character/author says, the only overt, deus ex machina-style salvation he will provide for his characters. Which seems kind of suicidal of him, considering that the Crimson King's plot to break the worlds would plunge his world into chaos as well and his novels are somehow vital to the success of Roland's quest. But let us not strain logic overmuch when we've already taken a ride on an insane supersonic train named Blaine. Because King the author is about to drop a much bigger deus into the story.

Roland and Susannah find that Dandelo has been keeping Patrick Danville, the boy saved in Insomnia, a prisoner in his basement. Now a young man, Patrick has the ability to make his drawings real. He will use this ability to draw and then erase the invulnerable spirit-being of the Crimson King, so that the major antagonist of the series, the one behind more evil machinations than one could shake a very discreet stick at and who nearly took over Susannah Dean's mind when she merely stepped into a sightline of his castle a book or so ago, will simply vanish, destroyed by a character who's been in less than one percent of this seven-book series and who disappears himself soon after. We're told Dandelo removed his tongue to keep him silent, and perhaps that's because Patrick's an honest enough fellow he would have said, "Stop reading here unless you want to feel really hornswoggled by this whole thing."

The move from story to story about story seems to leave King out of gas as he brings Roland nearer the tower. I suggested that Song of Susannah is most notable for having not much of note happen. You might say The Dark Tower is notable for how much happens instead of what ought to happen. Yes, Roland and the ka-tet destroy the means that the King is using to break the Beams and scatter the Breakers. Yes, they escape the Dixie Pig, buy the lot containing the mystic rose and save Stephen King's life. But as noted above, the Crimson King more or less disappears from the story and then literally disappears to end his threat. The Man in Black, Randall Flagg, dies without ever confronting his enemy Roland. Roland's half-demon son Mordred, after two books or so of buildup, manages to trip over Oy long enough to get killed.

Most of Roland, Susannah and Oy's final journey from the Breaker facility at Devar-Toi to the Tower itself is a long, cold slog through a bleak, blank wasteland, kind of like driving through downstate Illinois in the winter. Or reading books 6 and 7 of the Tower saga. After King got Roland's ka-tet together and ready to go, he seems to have lost inspiration for getting them anywhere, even though he started toying with the concept of the meta-narrative instead of just plain old story. He's like the tour guide at a theme park on the last run of the day: He's seen this stuff and been talking about it for his whole shift and he doesn't have the energy to put a spark in it one last time, even if the tourists visiting for the first time haven't seen any of it before and would like a little bit more than "Please keep your hands and feet inside the tram at all times."

Unreasonable expectations cause part of the Tower saga's problems. Many Kingophiles seized upon it as King's contribution to serious literary work, and indeed it begins with an elegaic quality that books like Christine never tried to match. One frequent poster at one Dark Tower forum has as his signature, "Thus ends the greatest story ever told, and I say thankya," imitating the speech of the people of Calla Bryn Sturgis. Obviously a guy with my job appends that "greatest story" title to another Book entirely, but I'd find it just as laughable if I sold shoes. Those are the readers' problems, though, not King's.

Writing a story about story didn't have to cripple it, but King's skills weren't by themselves up to achieving that task well. My opinion that editors have long since stopped reining him in means that he had no real external ear to say, "Why don't you try this?" or "That's kind of fuzzy, Steve. What do you want me to get from this bit right here?" or "So why didn't Patrick draw Susannah some legs?" or "Why didn't the Crimson King throw the whole box of sneetches at Roland and overwhelm his gun?"

If I were to ever run a marathon, I wouldn't win, either in my division or in one for people twice my age. But if I finished, I figure I should get some credit for that. King has earned kudos for sticking with the Tower saga over 30-plus years and actually finishing it, rather than twiddling his thumbs with prequels and atlases and leaving his major work undone on his deathbed to be finished by another author (I'm talking to you, Robert Jordan). He deserves kudos for a series with one great book, one really good book and a host of good scenes even in some of the stinkers, as well as some fascinating themes, only a few of which I sketched above.

And so we can leave it at that, I think. Maybe not three cheers, maybe not two, maybe not even one and half, but just under that, to be fair. Something like, 1.459 cheers. Why that precise? Well, if you look closely, you'll see the digits add up to...19.

Thankee-sai, hope I have spoken true.

3. The Ugly

Dave McKean's photo-collage illustrations in Wizard and Glass. Man, I hate that book.